LONDON: Jaded journalists on Fleet Street used to say that some stories were just too good to check. That sentiment appears to have been reworked by venture capitalists on Sand Hill Road: Some stories are just too good not to back.

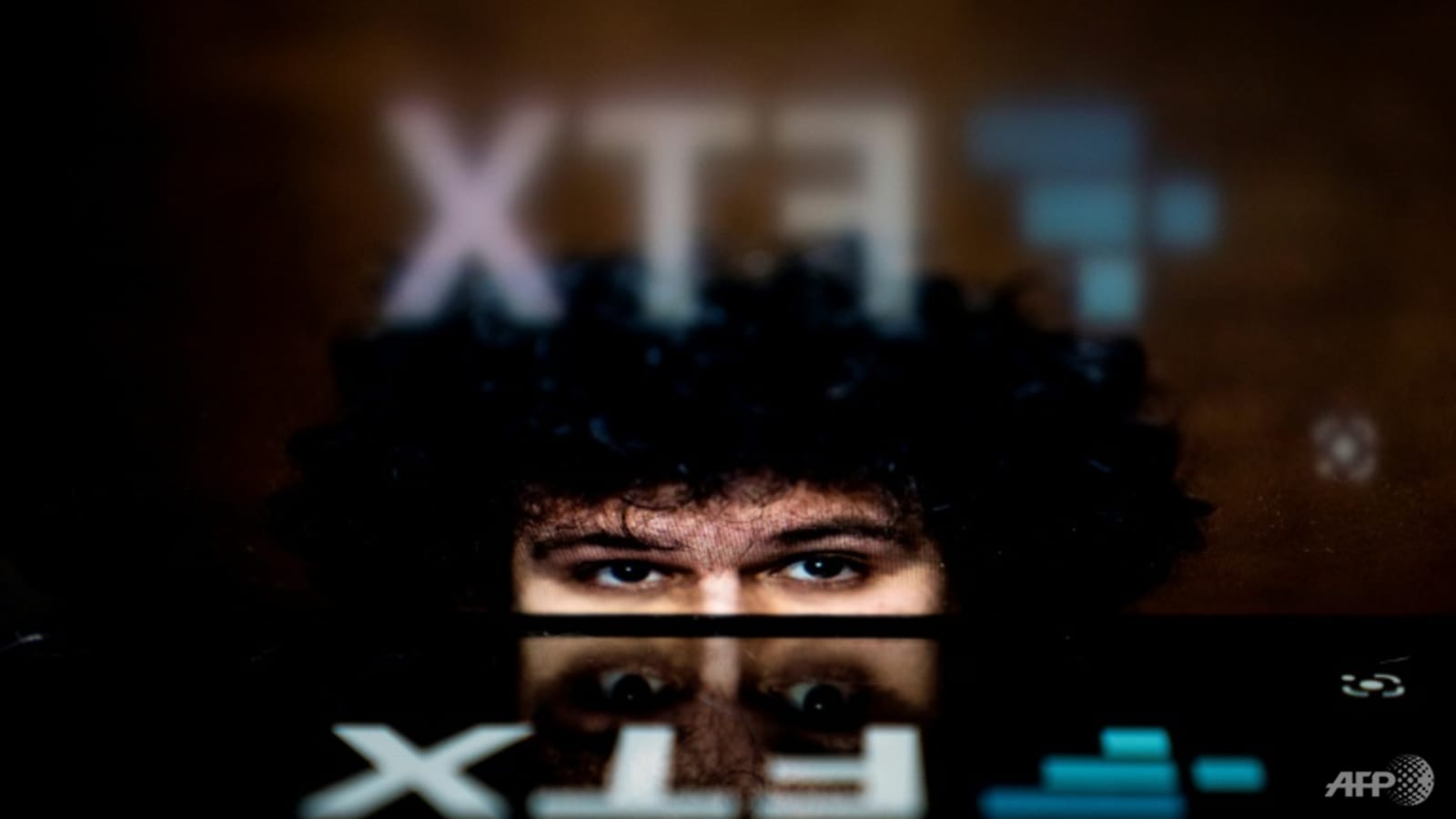

So it was with Sam Bankman-Fried: A seemingly brilliant and altruistic cryptopian who appeared to magic up money at will and promised to give it all away to the most needy. The trouble is that Bankman-Fried’s crypto trading empire FTX has now collapsed, swept away in a torrent of anger, recrimination and allegations of fraud.

At first, Bankman-Fried neatly fitted the pattern-recognition algorithm of Silicon Valley that decides whether big ideas are backed and start-ups funded. In many respects, he was the archetypal founder with his daring plan to disrupt the fat and lazy finance industry.

Son of two Stanford academics, a physics graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a risk-taking trader at Jane Street, Bankman-Fried had enough credentials to win him credibility. His somewhat obsessive, if not crazed, personality (reflecting the brain of Spock and the dishevelled appearance of Fozzie Bear according to one writer) added an endearing charm.

“OBVIOUSLY A GENIUS”?

A gushing 13,000-word profile of the founder commissioned and published by the VC firm Sequoia Capital, which backed FTX, was headlined: Sam Bankman-Fried Has a Savior Complex – And Maybe You Should Too.

His trading prowess in arbitraging away the “kimchi premium” between the price of bitcoin in Asia and the rest of the world was compared with that of George Soros. His plan to create an all-in-one financial superapp – and his bailing out of other troubled crypto companies – was likened to the ambitions of John Pierpont Morgan, who restructured finance for the industrial age.

One mesmerised Sequoia partner was reported as saying: “I LOVE THIS FOUNDER.”

According to PitchBook, a total of 86 investors, including Paradigm, SoftBank, Tiger Global and Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, backed FTX to the tune of US$2 billion. With a personal net worth of about US$24 billion, the 30-year-old Bankman-Fried was “obviously a genius” on track to become the world’s first trillionaire, the article concluded. (Since FTX crashed, the profile has been taken down, suggesting Sequoia’s belief in immutable records may be restricted to the blockchain).

DISTORTED REALITY

It was Apple’s co-founder Steve Jobs who was credited with creating a “reality distortion field”, exhibiting a head-spinning ability to convince anyone of practically anything. “The reality distortion field was a confounding melange of a charismatic rhetorical style, an indomitable will, and an eagerness to bend any fact to fit the purpose at hand,” one Apple employee wrote of Jobs.

That set a myth-making pattern that several entrepreneurs have since tried to mimic – with mixed success. Elon Musk has perhaps been the most Jobs-like in bending reality to his will at Tesla and SpaceX (although reality is proving more resistant at Twitter). But Adam Neumann at WeWork, Elizabeth Holmes at Theranos and now Bankman-Fried at FTX have all tried, and spectacularly failed, to sustain a similar reality-distorting trick.

At FTX, it is now clear that investors should have discounted the crypto hype and dug deeper into the interconnections between FTX’s trading platform, its Alameda Research trading fund and the crypto tokens it created. They might also have questioned whether Bankman-Fried, who boasted that he would never read a book, really was the visionary who was going to revolutionise finance.

Their hubris detection meters should have started twitching when celebrities and fading political rock stars, such as Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, flocked to his lavish conferences. And FTX’s Super Bowl commercial indirectly comparing Bankman-Fried with Thomas Edison should have moved the meter’s needle into the red.

After researching the world’s few, uncontested, geniuses, Yale University historian Craig Wright concluded that we need better metrics for identifying remarkable talent.

High IQ scores and degrees from prestigious universities have historically proven poor indicators: They generate too many false positives and false negatives.

As one undisputed genius Albert Einstein is supposed to have said: “If you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

The ability to extract large amounts of money from credulous investors and bilk your customers may count as a particular, if perverse, skill. But it does not count as any kind of genius.

How does restricting “high-risk” cryptocurrency sit with Singapore’s position as a fintech hub? Listen to CNA’s Heart of the Matter:

Source: Financial Times/aj