SINGAPORE: James Ho starts his days at 7am seated outside a McDonald’s outlet in Woodlands, waiting for a food order to come through.

“7am is actually a crucial timing. That’s when the breakfast crowd comes in,” said the 50-year-old delivery rider.

He turned to food delivery three years ago when the pandemic impacted his job in the food and beverage industry. During that time, his father died and he wanted a job that allowed him to spend more time in the day with his mother.

But for all the talk of quick cash, flexibility and control over one’s working hours, Ho is finding gig work to be a little disappointing.

After 8am, his delivery jobs slow to a trickle until 11am. That’s because Grab, the platform he’s with, ranks its food delivery partners and Ho’s ranking does not accord him priority for jobs during that period, he told Talking Point host Steven Chia, who shadowed him for two days.

On the first day, their shift was cut short after earning a mere S$17.30. The next day, they pocketed S$37.30 after 10 hours and seven bookings.

Chia’s stint was part of a Talking Point special, Beyond Plain Sight, that explores the harsh realities of some Singaporeans: Food delivery riders, children living in rental public housing and millennials on the brink of debt.

With Singapore’s platform workforce standing at some 73,000 workers — of whom over 16,000 do food deliveries — the programme looked at what it takes to earn a decent wage in the gig economy, and why not all riders benefit the same way.

WATCH: Working As A Food Delivery Rider: Are We Paid Enough? (23:01)

IS IT THE ALGORITHM?

Ho, who works solely on Grab and in the Woodlands area where he lives, feels that the platform’s algorithm has not been to his favour.

Under the platform’s shift system, riders are ranked and it affects how jobs are distributed.

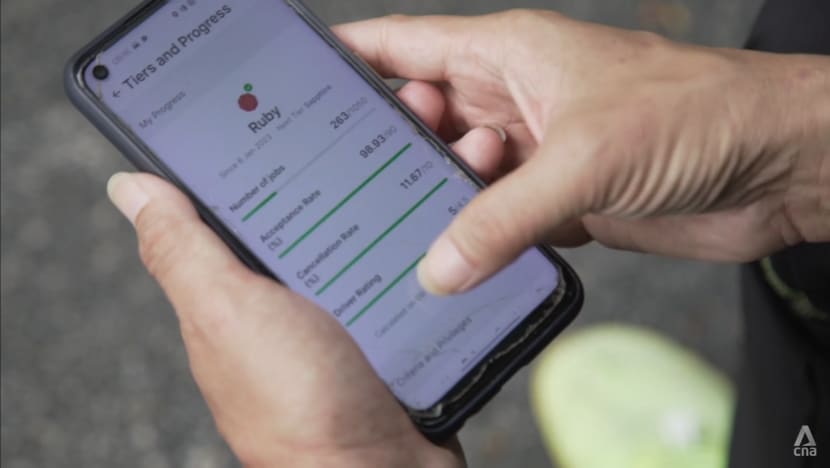

Ho, for example, is in the “ruby” tier, which is level two out of four on the platform. Newbies start off at the emerald tier and work their way up to ruby, sapphire and diamond based on several factors: The number of jobs they take, their job acceptance rate, cancellation rate and rating.

The higher the tier, the more benefits riders get and the more they earn. They get to book shifts and receive priority orders during certain timings.

Being able to book a shift also guarantees riders a minimum amount they can earn during that period, based on their location. Should their earnings fall short of the minimum fare, Grab will top it up.

Riders who are not on shifts may still receive orders — but as Ho experienced, the lull can be long enough for coffee breaks between deliveries.

Riders who reach a higher tier have to maintain a minimum number of orders to avoid being downgraded. To move up a rank, on the other hand, has proven difficult for Ho. He has been stuck in the ruby tier for a year.

The idea behind the shift feature, is that in exchange for the commitment to deliver in an area during specified hours, riders get some income assurance, said Grab’s group managing director of public affairs Lim Yew Heng.

Those in the higher tiers tend to be “more reliant on Grab as an income (source)”, he added. “So, we think it’s also important that priority allocation and privilege… is ringfenced for these more committed people.”

On Ho’s situation, Lim emphasised that, incentives or not, drivers are paid “fairly”.

There is a “base fare” that ensures riders’ efforts are “equitably accounted for”, he said. Grab’s “base fare” is benchmarked to the food and beverage industry, which is “something like S$1,400”, he added.

Besides being excluded from some shifts, what affects Ho’s earnings is stacked orders — when riders pick up multiple orders and deliver them all at once. In his delivery zone, Ho estimates that each order in a stacked order could earn him about S$3.90, while a regular order could earn him about S$5.

When there are delays during delivery, such as when he’s waiting for an order, or if a customer is uncontactable, it eats into the time he could have spent picking up another order.

Ho makes S$1,600 to S$2,000 a month, but there are the out-of-pocket shocks. On the first day Chia tagged along, the gears in Ho’s electric bicycle malfunctioned after five hours and four bookings.

“Our day is over, Steven,” he lamented. He had made only S$17.30 for the day, but the repairs would cost S$120.

HUSTLE, BUT AT WHAT COST?

Some riders such as 26-year-old Hasteven Jeremiah Anandan have fared better. He started doing food delivery full-time three years ago, and has upgraded his laptop to a gaming computer, got a deejay set and a thousand-dollar bicycle.

“I feel like I wouldn’t be able to actually afford all these things if I didn’t have a job as food delivery rider,” said Anandan, who has a diploma in business management. He hustled eight to 10 hours a day, five to six days a week, on both Foodpanda and Grab.

But the days of higher pay and better incentives seem to be over. He could previously earn up to S$4,000 a month, but the average these days is S$2,400 if he works full-time.

Starting the work day is not as straightforward as firing up the app and waiting for an order. Anandan has to plan his day around each platform’s algorithm.

On Foodpanda, he has to book a shift beforehand in order to pick up orders. Even then, riders can only book shifts by their batch number, which is allocated to them based on their performance each week.

One performance indicator is “actual versus planned hours”, which evaluates how many hours riders actually fulfilled during their shift. It takes into consideration late log-ins, no-shows and breaks.

“It’s something like a clock-in, clock-out system,” said Anandan.

These days, he finds it harder to secure shifts or long-enough shifts compared to the early days of the pandemic. He attributes this to more riders in the system. In between shifts, Anandan turns to Grab.

What he also guns for is surge pricing during peak periods, even on rainy days. While a regular order in his usual area in Serangoon would earn him about S$4, surge pricing could earn him about S$6.50, he said.

On a rainy day when he earned around S$50 from seven orders, Anandan remarked: “Really, really good for a lunch shift.”

Riding in the rain could mean more money, but Anandan is aware that dangers lurk. “The floors are slippery. And our bikes actually tend to skid when we brake too hard… it may be a little bit more dangerous on the road,” he said.

Riders may try to fulfil more orders during surge periods or rush to complete an order for a complaining customer, which makes them more accident-prone.

WATCH: Food Delivery Hustle: Is It That Lucrative? How Much Can You Make? (22:04)

Between January 2021 and July 5 last year, five food and goods delivery platform workers were killed in work-related traffic accidents. And a survey by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) last year of 1,002 food delivery workers found nearly one in three of them had been in at least one accident serious enough to require medical help.

Lim said Grab is “very conscious” of how its incentive scheme is designed. He added: “If we start to see that (riders) are you know, behaving in such a way that it’s dangerous… in some cases, we actually block them from driving.”

THE SUSTAINABLE WAY FORWARD?

The IPS survey —the first ever on platform delivery riders — also found two-fifths of the respondents would leave the industry “as soon as possible” if they had other job opportunities.

Seven in 10 respondents earned less than S$3,000 a month, and more than one in three would leave for a job that pays them at least that amount.

With the “evolving platform business models”, riders do not really have a say in how much they earn, said Member of Parliament Yeo Wan Ling, advisor to the National Delivery Champions Association.

“That’s why at the end of the month, unlike salaried employees, our platform riders don’t really know how much (they’re) taking back for that number of hours that they’re working,” said Yeo.

They are also unlike freelancers who decide how much they want to charge and when they want to work, she noted.

To make riders’ income less volatile, platform companies could look to Germany, suggested Abel Ang, an adjunct professor at Nanyang Business School.

“Because of the control that platform companies have (over) the riders, the courts in Germany indicated that… platform companies have a responsibility to provide the implements or the tools for the riders to actually do their work.”

These include a smartphone and a bicycle, said Ang.

IPS principal research fellow Mathew Mathews, who led the survey’s research team, believes people should engage in platform work on “a more part-time basis”, such as those who have just been laid off.

But the survey found that 46 per cent of respondents relied solely on food delivery for income.

A large proportion were newer riders, with 32 per cent having spent less than a year on the job and the same proportion having worked two to three years.

The long-term impact of working as a delivery rider is being stuck with a “very low socio-economic status”, he said.

They do not get the increments and bonuses other workers receive, or make contacts who can connect them with better opportunities, said Mathews. The career prospects are “nearly nothing”, he said.

Whether you’re working on the platform for 10 years, or one year, pretty much the same skill set.”

The Ministry of Manpower has announced new measures for gig workers from 2024. They include requiring platform workers below the age of 30 to contribute to their Central Provident Fund accounts, so they can save up for retirement and housing. Older workers may opt in.

Riders will also be compensated for their earnings if they get injured on the job.

IN SEARCH OF A BETTER GIG

Anandan said he has enjoyed the “really good money” from being a full-time delivery rider, but does not see himself doing this beyond the next two years.

“Working as a food delivery rider feels a bit stagnant and there’s no progression towards the future,” he said, echoing Mathews.

He has transitioned to doing food delivery only four hours a day, and spends the rest of his time on a “side hustle” providing engraving services. He hopes the latter will one day be his ticket to “financial freedom”.

Ho is also seeking out other opportunities. His income from delivering for Grab is just enough for himself and his mother, with nothing left to set aside for retirement.

But without a “high education level”, he has faced obstacles. He’s sent out his resume to potential employers, but worries he has “lost touch” with the job market. When he tried to upskill and attended a course in security, he “flunked” the final paper and “couldn’t make it”.

Returning to the food and beverage or events management industries is another option.

But even with relevant experience, he does not feel “100 per cent confident” gunning for the role of food and beverage supervisor, he admitted. “I keep asking myself, do I still (meet the) criteria?”

Watch the Talking Point episode with Ho’s story here. Watch the episode featuring Anandan here.