It is the exhibition that we at AUGUSTMAN have been waiting for: a presentation at the intersection of history, culture, art and fashion. It is an exhibition especially relevant to our region, but as we walked through its displays, it becomes clear that this exhibition celebrates a worldwide phenomenon.

Welcome to Batik Kita: Dressing in Port Cities. Located in the second level of the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM), this presentation of batik cloths and batik fashion pieces from our region and beyond is put together by Senior Curator Noora Zulkifli and Guest Curator Lee Chor Lin.

For Chor Lin, it is a sort of homecoming. The museum veteran, hailed for rejuvenating Singapore’s museum scene during her tenure as Director of the National Museum of Singapore from 2003 to 2013, returns to the museum where she managed the China and Southeast Asian galleries from 1997 until 2003. For her work as a custodian of both regional and international heritage, culture and history, Chor Lin was conferred the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters) by the French government in 2008 and Cavaliere, Ordine della Stella d’Italia by Italy in 2012.

When we sat down for a chat with her after touring the exhibition, she was every bit – and more – the erudite, eloquent history scholar we expected her to be.

“Singapore is a natural venue for a presentation like this,” said Chor Lin. “Yes, batik is deeply rooted in Javanese culture, but it was also an internationally traded product, and a lot of them would go through our port. Before World War 2, when Singapore was primarily an entrepot, millions of rolls of batik would come through Singapore before being exported to the rest of the world. Even so it’s not just something in the past. We’ve worn batik ourselves, or have seen friends or family members wear them. It’s part of our personal lives. It’s part of us, here in the present.”

Regional Roots, Global Appeal

The term ‘batik’ refers to both the technique of wax-resist dyeing that creates its prominent designs, as well as cloths and fashion pieces that feature designs created with the technique. It is recognised by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. While many rightfully associate ‘batik’ with Java or perhaps the Indonesian islands at large, its methods, as they are known today, are a result of a cross-pollination of ideas from different cultures and nations.

“The earliest batik were made with rice paste or a combination of rice paste, glue and mud. But they didn’t last long nor did they allow for very fine work,” Chor Lin explains. “If you look at pieces from earlier in the history of batik, they feature very rough strokes.”

She continued, “But the Javanese learnt that beeswax, when melted and applied through a canting (a traditional hand tool to apply molten wax, as pictured below), allows for finer drawing – thinner lines and therefore more complex designs. And they got beeswax from trade with countries in the region with a strong Catholic presence such as the Philippines and Borneo, who were using beeswax to make candles for their chapels and churches.”

Merchants from Europe, India and Japan eventually brought in chemical dyes as well, and this allowed the artistry of batik to flourish even more.

Europe’s industrial revolution also helped. The Dutch, Indonesia’s colonial masters of the time, brought in steam-powered machines and industrial woven cloth into Java, facilitating the proliferation of batik not just regionally, but around the world. With Singapore as entrepôt, batik spread around the world, to the rest of Southeast Asia, Europe, Africa and even the Americas.

“There were textile magazines in America that would feature articles on batik. The word ‘batik’ was already in the English lexicon in the 1920s,” said Chor Lin. “Batik isn’t just an art form. It’s a commercialised art form that people traded. And it was popular because back then, it was one of the most readily available ways for people to wear patterns or colours in their clothing.”

A Symbol of Status and Power

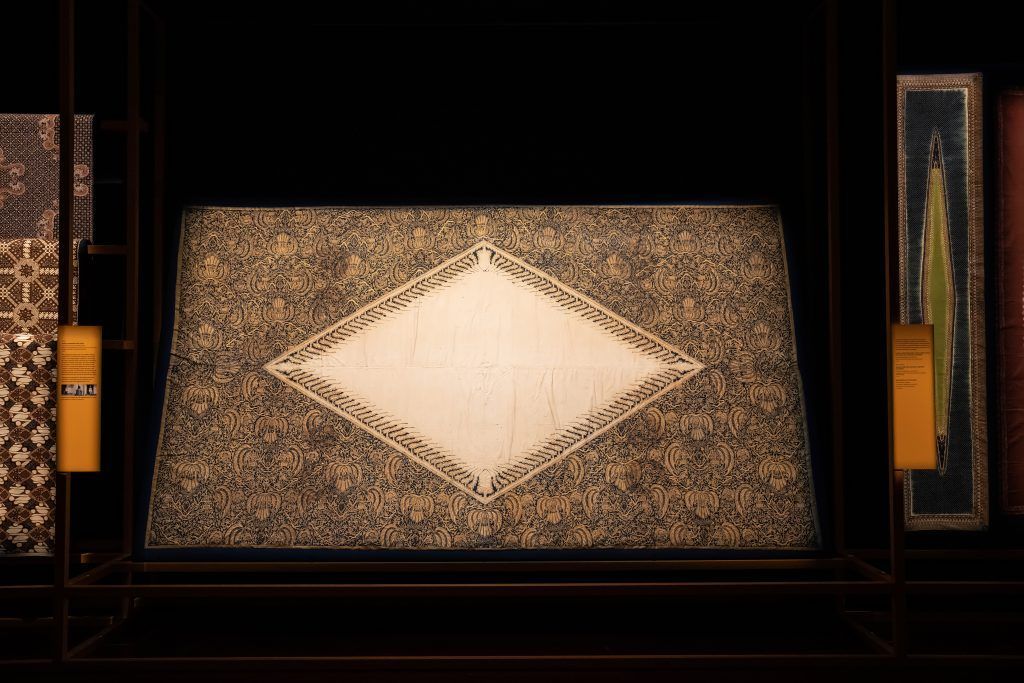

The first thing that greets you when you enter the Batik Kita exhibition is the magnificent 2m X 4m dodot, or ceremonial waist cloth typically worn by Javanese rulers and sultans. Every detail of the work speaks to the noble virtues embodied by its wearer.

The white lozenge-shaped tengahan or centrepiece represents the ruler’s spiritual purity, while its central position is symbolic of his place as the focal point of the universe. The perimeter of the tengahan features a flame motif, guarding the wearer’s purity. The rest of the cloth features the elegant gold leaf motif that speaks to his worldly wealth and status. Instead of the wax-resist methods of modern batik, the motif is applied with fish bone glue, a more primitive method of batik. While its age does show, it is nevertheless well-preserved, a testament both to its craftsmanship as well as ACM’s custodianship.

The dodot is significant to Singapore’s museums collectively. It was one of the first pieces to arrive at the Raffles Library and Museum almost 100 years ago in the 1920s. The Raffles Library and Museum is the predecessor to the modern, immaculately curated museums that can be found in and around Singapore’s civic district.

It was one of the first things Chor Lin wanted in the exhibition. “When I began speaking to the conservators, I said whatever we do, I must have this piece out on display because it is one of the earliest pieces to come to the museum. I want people to see how fine the work is. I want to tell people – this piece is over a hundred years old, but look at that workmanship.” She adds with a laugh, “There was a lot of bargaining with the conservators. I had to drop a lot of pieces for display in this exhibition just so the dodot can face the world one more time.”

The dodot wasn’t the only batik piece in the exhibition that spoke to the nobility of its wearer. Also on display is a large batik cloth adorned with the iconic parang rusak motif, one of the oldest batik designs, and a motif, at one point in Javanese history, only allowed to be worn by the ruler and his family.

Despite its name, the parang rusak, or broken blade, motif was inspired by the shape of waves breaking against a reef. The continuous S-shaped braid represents the eternal fight for good to prevail over evil, and the neverending struggle for self-improvement, just as the waves never tire in hitting the reefs. Meanwhile the straight diagonal lines of the motif symbolises respect, steadfastness and reverence to the truth. The size of the pattern also signifies the wearer’s social status in the realm of the kingdom.

These abstract designs and the philosophical connotations undoubtedly contribute to the timeless appeal of batik and gave power to plain cloth. But it is in its foray into everyday men’s fashion that truly cemented its relevance.

Batik In Politics and Men’s Fashion

“I think the batik shirt is the saving grace of Southeast Asian men,” Chor Lin proclaims. “Back in the 60s, it was a fashionable alternative to wearing a suit to work, especially considering our climate. It didn’t make sense to wear suits to work in this part of the world.” Back then, batik shirts were also a symbol of our regional identity, in an era when more and more nations in our region were gaining sovereignty from their respective European colonisers. To wear a batik shirt instead of an European suit was an expression of our independence. Indonesia and Malaysia made batik the standard for official and work wear. Singapore encouraged but did not officialise batik for official wear. “Nevertheless, our leaders were savvy,” said Chor Lin. “They understood what batik meant to the region, so they adopted it for regional official events.”

In the Batik Kita exhibition, menswear – particularly batik shirts – by batik couturiers Iwan Tirta, Baju by Oniatta, Rasta Rashid and Sarkasi Said are on full display, including some pieces worn by political luminaries from our region such as Singaporean Prime Minister Mr. Lee Hsien Loong and former Malaysian Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad.

One that stands out was the red-and-white batik shirt designed by Singapore Cultural Medallion recipient Sarkasi Said that Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong wore at the National Day Parade in 2019. The bold colour choice – not unheard of, but nevertheless rare – seemed almost representative of Singapore’s leadership at the time: daring, modern, building on the traditions and norms that preceded it.

Also on display are the silk batik shirt worn by Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Bogor in 1994, an event that also saw then-US President Bill Clinton wear a batik shirt. The shirt worn by Mr. Goh was an eye-catching number, a black base with a vibrant golden-orange fern leaf motif.

More importantly, the exhibition also shows bold new ways of wearing batik that combine both the ideals of modern fashion as well as the expressions of identity. Take, for example, BINhouse’s pagi-sore (morning and night, pictured below) motif sarong that utilises colour blocking to brilliant effect, combined with a more traditional batik scarf. It is a deconstruction of batik in menswear. Instead of going along with the batik shirt, the sarong and scarf preside here, providing a colourful, spirited expression of one’s aesthetic leanings. Perhaps not suitable for a formal occasion, it helps the wearer stand out brilliantly at cultural events and casual soirees.

Just as compelling is the aptly named Merdeka (Freedom) Jacket from Baju by Oniatta, paired with the Utama Pants from the same Maison. Equal parts beach or loungewear and equal parts statement piece, this versatile ensemble invites its wearer to partake in our regional culture while retaining a modern, masculine expression.

These, and more, are some of the pieces available for public viewing at the Batik Kita exhibition. It’s as much a trip through history as it is a rallying call for modern fashion – especially men’s fashion – to truly embrace batik. With that in mind, Batik Kita is a well-timed exhibition and a must-add to your calendar.

“A large scale batik retrospective like this has been a long time coming. Batik is enjoying a renaissance today,” says Chor Lin. “I hope that Batik Kita is just one of many more beautiful batik exhibitions to come in Singapore.”

The Batik Kita: Dressing in Port Cities exhibition runs until 2nd October 2022 at the Asian Civilisations Museum (1 Empress Place Singapore 179555).

For more information, visit https://www.nhb.gov.sg/acm/whats-on/exhibitions/batik-kita

This story first appeared on Augustman Singapore

The post The batik exhibition at the Asian Civilisations Museum is a rallying call for modern fashion to embrace this age-old technique appeared first on Prestige Online – Singapore.