Advertisement

What does it take to keep one of Singapore’s oldest chicken rice brands alive? For its third-generation owners, large pay cheques aren’t the only sacrifice.

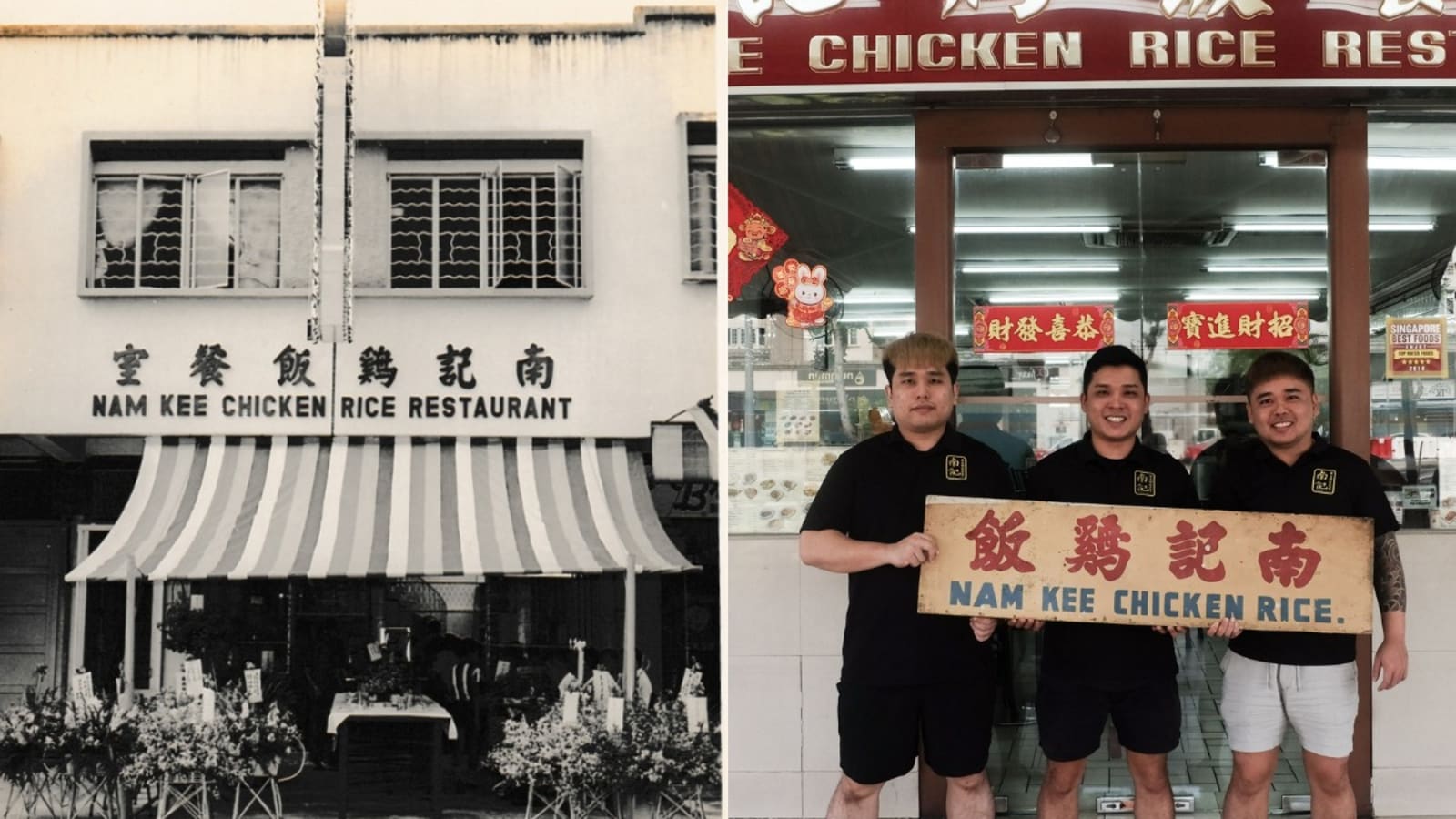

Nam Kee Chicken Rice Restaurant opened in 1968, and is now run by the founder’s grandsons Lincoln, Dave, and Ken Chew. (Photos: Nam Kee, Joyce Yang)

When the Chew siblings told their superiors at the bank that they were leaving to sell chicken rice, the latter thought it was a joke.

“My big bosses actually got angry,” said 32-year-old Dave Chew. He had earlier roped his elder and younger brothers, Lincoln and Ken, into the same bank, where they became top performers in the same department and reported to the same people.

“They said, just tell me which competitor is poaching you. You don’t have to tell me stupid things like you’re going to sell chicken rice.”

Only when their bosses saw them slogging at Nam Kee Chicken Rice Restaurant did they buy it. While their disbelief is valid, so are the trio’s reasons for giving up lucrative careers to take over their father’s business – during the pandemic, no less.

To find out what they are, CNA Lifestyle spoke to Chew Chee Juai, the restaurant’s second generation owner, and his three sons.

ONE OF SINGAPORE’S OLDEST CHICKEN RICE STALLS

Nam Kee Chicken Rice Restaurant – not to be confused with a competing restaurant chain – was founded on Hainan Island by Mr Chew’s late father before finding its way to Upper Thomson in 1968. He was only six years old.

“Before Singapore modernised, Thomson was quite secluded. We were surrounded by kampungs and they only built shophouses later,” the 61-year-old said.

They were tenants at coffee shops, selling Hainanese chicken rice and zi char, before taking out a bank loan to set up a restaurant. “We were probably the third or fourth chicken rice stall in the country, but the first to get registered.”

Along with three elder brothers, Mr Chew started working at the restaurant in primary school because his parents could not afford help. They worked 14 hours every day, pausing to catch their breath only on the first day of the Chinese New Year.

“We got up at 4am to buy chicken from Tekka Market. You had to arrive early to get the cream of the crop,” he recounted. Before central suppliers entered the picture, they had to know the varieties of chicken and rice by heart and process the poultry – from culling to cleaning – in house.

“It was a traditional business, so every one of us had to know it inside out. Sometimes, we would toil away till midnight. Life was tough before Singapore became prosperous.”

A BELOVED VENUE FOR FAMILIES

Even with a 55-year institution under his belt, Mr Chew is reluctant to define what makes his chicken rice or zi char authentic.

“Technically, the Cantonese, Hokkien and Hainanese styles of zi char are different, but that has become a lost art since. They’re practically one and the same today, but we hold on to tradition by making our sauces and pastes from scratch,” he said. This applies to their signature chilli and seasoning for Hainanese chicken chop, and sweet and sour pork.

Mr Chew insisted against wholesalers, fearing that Nam Kee’s homemade quality would be eclipsed by the dazzle of speed, convenience and volume. This single mindedness appears to run in the family, seeing as how his father had turned down every last franchising opportunity in Thailand, Japan and Australia for similar reasons.

“My father was a conservative man. To him, quality will certainly suffer if we branch out.”

That didn’t stop them from drawing an international crowd, and customers in the early days hailed from as far as the United States and United Kingdom. They must have gotten here by word of mouth, since his father rejected advertising and declined all interviews with the media. Apparently, few restaurants served chicken rice and zi char in one place then, making Nam Kee a beloved venue for large gatherings.

That also explains why their clientele comprises mostly seniors in their fifties or sixties. Many of them first visited the restaurant as kids and now bring their grandchildren here for meals. In fact, a final meal at Nam Kee was the dying wish of one such elderly customer.

“He was critically ill, and insisted that his son bring him here for a last meal at Nam Kee. He passed away after returning home. We are deeply moved by this story,” recounted Mr Chew.

THE CHEW BROTHERHOOD

Many regulars have watched Dave, Lincoln and Ken grow up, which is unsurprising considering how much of their adolescence was spent in Upper Thomson.

“My brothers and I used to catch fish in the large drains. There was a sense of safety because wherever we went, neighbours in the area knew us as our father’s children,” Dave recalled. The restaurant was his father’s way of keeping a young, wayward Dave out of trouble. He had to earn his own keep or go to school with no allowance.

“I have spent every weekend here since I was in Secondary 2. Even when I was serving NS and working full-time at the bank, I did so without fail. My whole life is here.”

But succeeding their father was never in the cards. If anything, they were compelled to explore the world out there. It is mildly comical that their lives remained inextricably linked even after leaving the restaurant; picking similar majors in school and landing identical roles at the same bank. When one brother jumped ship, two followed suit. Naturally, when Mr Chew first spoke of retirement two years ago, they were on the same page.

“My parents got emotional one evening at dinner, saying it would be a pity to close the restaurant that had single-handedly provided for four families. My mum even teared up, which was heartbreaking to watch. That was when we realised Nam Kee is more than a business; it’s a family legacy.”

But they had to act fast, for Mr Chew already had an offer and a cheque in hand. For two weeks, they convened every night for discussion. Was it unwise to forgo their high-paying jobs for the cutthroat F&B industry? Were they ready to leave their cushy offices to rough it out in the kitchen?

“All the risks were on the table, but we came up with a plan. The uncertainty was still there, but we always believe that if we want it, we will do it. It is that simple,” said Ken, who is 28 this year.

Their mum’s joy came with a fair share of worries. For decades, she alone held the fort at home while Mr Chew toiled away from dawn to dusk. She feared that by following in their father’s footsteps, her sons would likewise compromise time with their spouses and children.

“I think we’ve only gone overseas together once in my whole life. We went to Bangkok when I was four to five years old,” said Dave. Mr Chew sometimes took the boys out for supper after drawing the shutters, but that was as far as family outings went. He also missed the boys’ convocations, along with other milestones.

“I was really swamped and it couldn’t be helped. Everyone’s background is different,” Mr Chew added. He had been the family’s sole breadwinner for decades, working 364 days a year without rest to give them a better life. Obviously, his boys’ interest in a similar undertaking shocked him.

“They were making good money and there was no reason to enter the F&B industry. It’s hard work and high levels of stress. But, since they are adamant, they should be given a chance. They’re on their own from here on out. We’re getting on in age, and it’s time for us to take a backseat.”

PASSING THE TORCH

The brothers took over right as the pandemic tore the F&B industry apart, grappling with a near 100 per cent pay cut and steep learning curve. Mr Chew’s philosophy was this: Only when you master every aspect of a business are you ready to run it. Knowing how to cook was not enough; they had to do the menial stuff. Taking the trash out, doing the dishes, and plucking the green tops off fresh chillies were part of the deal.

“It seems straightforward, but if we didn’t do it, we wouldn’t be able to tell when the chilis are soggy. Rice has different grades, too. When we wash it, we’ll know when it isn’t the grade we normally use and call our supplier immediately. That’s what our father wants us to learn, but he’s not expressive enough to say it,” Ken said.

While the second and third generations are aligned on their “probationary” duties, they didn’t see eye to eye on plans to digitise. Nam Kee wasn’t on a single delivery platform before the pandemic. The restaurant had no iPads, either. For the longest time, Mr Chew took orders and issued invoices by putting pen to paper.

“We’re in a tech era, but my father doesn’t see it until we sit down and talk to him logically. Even though he says no sometimes, he still helps us and gives us the support we need.”

Against a backdrop of inflation and rising costs, their recommendation to increase prices was another point of contention.

“He said, we can’t do that. Our customers will be angry. My father thinks for the customers rather than himself. He was concerned that our regulars wouldn’t be able to afford it. That’s the kind of person he is.”

As it turned out, their regulars have shown nothing but understanding for the business and support for its new showrunners. Doubtless, the current economic climate isn’t the best timing for the latter. But to Mr Chew, it’s a mere blip in the timeline.

“On this journey, Nam Kee has weathered many storms. The bird flu, swine flu, and many economic downturns forced many competitors to shut down. But we kept going even when the business wasn’t profitable. We had to keep our tradition alive.”