SINGAPORE: Strings of data comprising 1s and 0s may look like gibberish to the untrained eye, but Mr Ng Junsheng knows the “organised mess” hides clues to what may have caused a plane crash.

The senior air safety investigator with the Transport Safety Investigation Bureau (TSIB) dives into the data once it has been translated into individual parameters – pitch angle, time, speed and power, among others – to look for “relationships”.

If “things were normal”, for instance, the data would show a corresponding output when the pilot moved a particular switch in the cockpit.

But if there were no corresponding output recorded for the pilot’s command, “that may be a clue that something did not go well” and “we will then continue to probe deeper into that area of interest”, explained the 42-year-old, who also manages TSIB’s flight recorder readout facility.

The facility, which was set up in 2007, made headlines when reports highlighted its role in investigating Nepal’s Yeti Airlines plane crash in February. It would help Nepalese authorities to retrieve and process the data readout from the flight recorders.

A flight recorder – commonly known as a “black box” – is an electronic recording device placed in aircraft to aid in the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. It comprises two sections: The flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder.

In response to TSIB’s assistance in the Nepal investigation, several social media commenters said they did not know Singapore had such a facility – and neither did Mr Ng when he responded to a TSIB job advertisement 10 years ago out of curiosity.

A decade later, this same curiosity still drives him to uncover the larger story behind binary numbers and soundwaves.

MAKING SENSE OF NUMBERS, AUDIO FILES

Think of the flight data recorder – one of the sections in the black box – as the “digital data of the aircraft system’s health”, Mr Ng told CNA, pointing to three screens across which the data is laid out for investigators to look at one go.

This information, once downloaded, is presented as “a whole bunch of 1s and 0s” on one screen. A recorder specialist then translates the data into “usable units” before proceeding with a “holistic” analysis of these parameters.

An adjacent screen displays charts highlighting the relationships between the individual parameters, allowing the team to “understand what the pilots did, the system status and what changes were made to the aircraft configuration”, he added.

A third screen, with an animation from the pilot’s perspective, can help stakeholders better visualise TSIB’s findings.

But Mr Ng explained that investigators do not depend on the animation to piece together what may have happened. It may skew their conclusions; the fair weather conditions presented in the animation might differ from, say, a stormy night in reality.

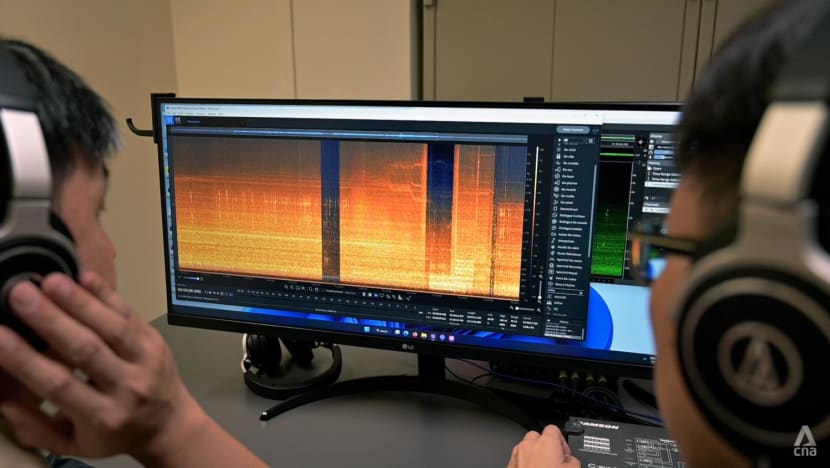

The other section in a black box – the cockpit voice recorder – contains a recording of all audio communication within the cockpit itself, said Mr Ng.

“It typically gives us an insight into what the pilots spoke with each other, and the pilots’ communication with the external environment, such as with the air traffic controller, cabin crew and potentially other aircraft.”

This data is presented in four separate tracks, which investigators input into the system to transcribe. If all is well, investigators are able to instantly listen to and analyse what is on the tracks.

When there is too much noise, however, they have to apply “special techniques” that involve “removing specific noise information” in an attempt to uncover the audio that was recorded, he said.

There are more uses to voice data than one may expect, added Mr Ng, highlighting a portion of an audio track.

“At times when the conditions are challenging or it’s not recorded on the flight data recorder, we can actually spot specific bits of information and that may lead us to understand that certain levers were moved,” he said.

“Looking at the individual striations in this graph, you can actually do a back calculation to determine the speed of certain gearboxes or the propellers itself.”

All in, the combination of voice data and parametric data “allows us to have a much better view of what actually happened in the cockpit and potentially understand the circumstances of the occurrence”, he added.

RECOVERING A BADLY DAMAGED FLIGHT RECORDER

But not every flight recorder comes to TSIB in a “wonderful condition where everything is serviceable”, said Mr Ng.

In some cases, the flight recorder may be “badly damaged”, such as when the aircraft has plunged into the ocean. In other instances, investigators may be hampered by external elements, from the weather to a lack of funding.

“There is a process known as sea search recovery to retrieve the recorders and the wreckage. This process itself tends to be pretty tedious and cost-intensive,” he said.

“For investigators on the teams going out to conduct the investigation, the elements may be against you. There may be torrential rain, there may be massive sea waves. And also, the cost itself may sometimes mean that the process has to take a slower pace because the investigation agency or the partner agencies need to look for funding.”

During the sea search, a hydrophone is used to detect the “sonar pings” from an underwater locator beacon, which is usually fixed onto a flight recorder, added Mr Ng.

At TSIB, digital software allows the data to be collected and processed in real time, allowing them to have a “rough idea” of where the flight recorder may be before they “zoom in” on the area.

And contrary to popular belief, the “black box” is not actually black. Instead, its bright orange colour helps divers to identify it underwater.

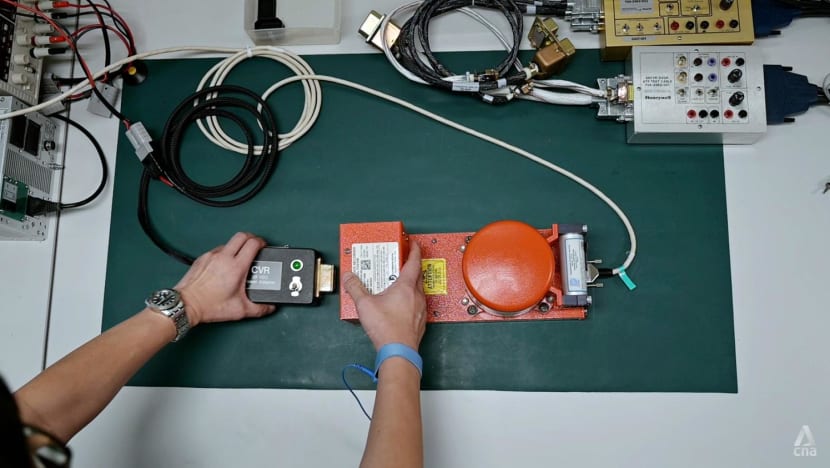

Once a badly damaged flight recorder is retrieved, the “sacrificial” parts are first removed.

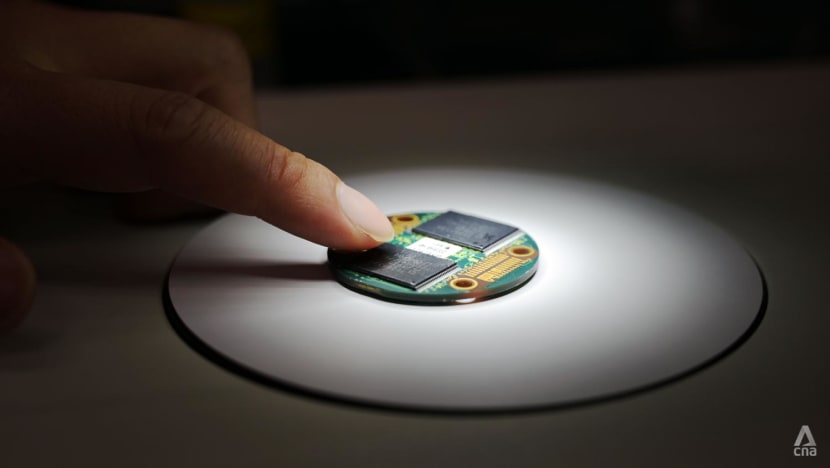

Then, recorder specialists “typically go for the memory chip” that is stored within a Crash Survivable Memory Unit (CSMU), said Mr Ng, adding that the CSMU will be removed and “transplanted onto another exemplar unit that’s working fine”.

The CSMU is the large cylinder that bolts onto the flat portion of the recorder.

After it is removed, electrical checks are then conducted to uncover further damages. For instance, if there are cuts on the ribbon in the memory unit, the ribbon cable will be “resoldered” to repair the connection, he added.

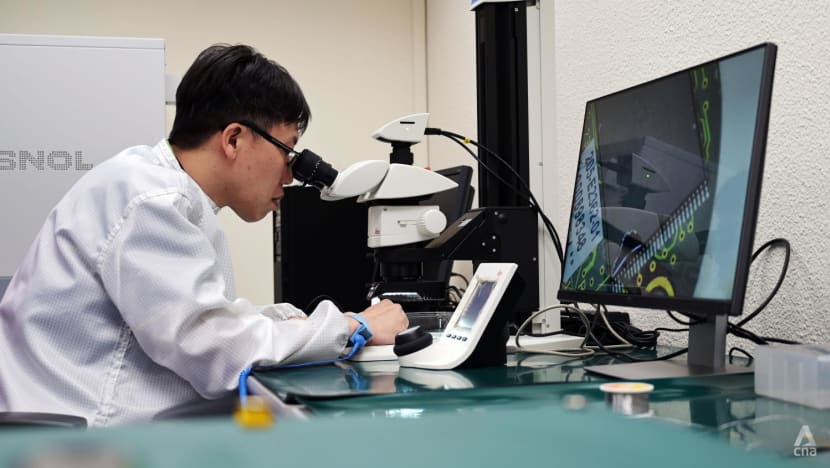

“In certain situations where there appears to be more significant damage to the memory chip itself, we will look at the chip under the microscope to look for cracks, damages or even debris that may affect or compromise the operation of the chip whenever power is being applied.”

Flight recorders that have been submerged in water are placed in an oven to dry at 50 to 60 degrees Celsius. It can take a few cycles before investigators are satisfied that the printed circuit board is “fully dry”. Then it’s reassembled into a good unit before investigators attempt to download the data, said Mr Ng.

That said, not every aviation incident requires examining a flight recorder.

For example, in a runway incursion when the aircraft was “just a passer-by in the event”, data is sought from other sources, like radar information from air traffic controllers, he added.

WHEN DOES TSIB GET INVOLVED?

While the Nepal plane crash may have put the spotlight on TSIB, the department – which is housed under the Ministry of Transport – doesn’t investigate every aviation incident.

Aviation investigators at TSIB get involved in “aviation accidents” or “serious incidents” that have “very specific definitions”, said Mr Ng, adding that TSIB follows the International Civil Aviation Organization requirements closely.

As defined on TSIB’s website, an aviation accident or serious incident is one which occurs in Singapore, regardless of the country in which the aircraft is registered. Alternatively, it occurs to a Singapore-registered aircraft or an aircraft operated by a Singapore operator when the aircraft is overseas.

“Our legislation does provide us with the opportunity to conduct an investigation, if there are incidents where we find that there are safety lessons to be learnt as well,” he added.

TSIB investigators are appointed as Inspector of Accidents by the minister under the Air Navigation Act and the Air Navigation (Investigation of Accidents and Incidents) Order for aviation occurrences.

In the case of the Nepal plane crash, Singapore’s Ministry of Transport and Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation had signed an agreement to cooperate on investigations relating to aircraft accidents in February 2020. The Memorandum of Understanding covers the use of investigation facilities and equipment, including the flight recorder readout facility.

There is an “international element” specific to aviation incidents in Singapore, said Mr Ng.

Any investigation involves several parties – such as the place where the incident took place, where the aircraft was manufactured or registered, and where the aircraft operator is based.

“You will have foreign investigators joining in, and they can be supplemented by subject matter experts, such as the airframe manufacturer or the engine manufacturer, to provide the expertise they have,” he said.

In 2016, a Singapore Airlines plane caught fire while making an emergency landing at Changi Airport. The aircraft was a Boeing 777-300ER, manufactured in the US.

TSIB – then known as the Air Accident Investigation Bureau – worked with its counterparts from the US National Transportation Safety Board to investigate the incident. Boeing was also involved in the investigation.

But Mr Ng stressed that TSIB is an independent body. Even though it sometimes runs parallel investigations or shares resources for logistical reasons with multiple agencies, each agency conducts an individual site analysis.

TSIB also does not have powers to enforce penalties, he said. They run a “no blame, no liability” investigation, with the primary goal to prevent a recurrence of a similar safety-related event.

INVESTIGATION PROCESS

A full investigation could span a few months to years for more complex cases, said Mr Ng.

It begins with field investigation, which involves collecting evidence through site photography, conducting interviews and getting documentation such as maintenance and training records.

Drones are also used to collect photos of a crash site. This has proved “very vital” because drones may find more wreckage that investigators may not have seen, he said.

Investigators also use equipment that produces 3D scans, allowing them to “recreate the occurrence site and the wreckage itself”, so “other parties can clear the site and normalcy can resume”.

All this, including reading the flight recorder, allows TSIB to “build a cache of information” to understand the circumstances surrounding the incident.

“We will then determine whether additional steps are needed, such as specialised testing, modelling or simulation,” added Mr Ng.

After this is done, investigators analyse the cases, develop hypotheses and test them for loopholes, before drafting a report. All stakeholders involved have a chance to provide comments on the draft, before the final report is eventually published on the Transport Ministry’s website.

MARINE, RAIL INVESTIGATIONS

While its aviation division is the most established, TSIB is also responsible for the investigation of marine and rail accidents and incidents.

It began as the Air Accident Investigation Bureau in 2002, prior to being renamed TSIB after expanding its scope to include marine investigations in 2016. Rail investigations were subsequently added in 2020.

Senior marine safety investigator Xiao Shouhai said marine incidents could happen out at sea, at a port or terminal; during navigation, cargo operations, bunkering or maintenance.

Explaining the possible challenges of investigating marine incidents, Mr Xiao said sometimes survivors could be in hospitals in “different places”. The seafarers on the ship also often come from many different nations, and only stay on the ship for a few months. This could make it difficult to conduct interviews.

In rail investigations, “the railway system is a system within a system”, added Mr Gilbert Low, a rail safety investigator.

“You have the track, the train, the signal. It’s a challenge to understand how each system affects one another and how to correlate the information and data,” he said.

“We also might see, in a massive railway incident, there is massive disruption. (With) information gathering and evidence collection, the time is against us. It’s about how we do it efficiently and properly to collect the perishable evidence, with the aim to resume the service and lessen disruption.”

Unlike aviation incidents where the usage of a flight recorder is more specific to investigations, data logged in the train recorder is used primarily for maintenance purposes. Its recorder also has “crash protected memory”, and is able to withstand shock and heat from a fire, added Mr Low.

PEOPLE SKILLS, EYE FOR DETAIL

As marine and rail investigation processes are largely similar to aviation investigations, from collecting evidence to conducting interviews, investigators from different disciplines often help one another.

Nonetheless, they come with relevant educational background and industry experience.

“In the aviation domain, we typically look at pilots, licensed aircraft engineers and also air traffic controllers. For the marine sector itself, we have ship captains with very rich experience. And for rail, we have people who have previously operated on rail systems,” said Mr Ng.

He noted that TSIB investigators typically work on “very large projects with many people” from different backgrounds, so having good interpersonal skills is necessary.

Individually, a good investigator should be objective and open-minded, as “a subjective person will typically be swayed”. They should be able to focus on the facts of the case and develop hypotheses “without being biased by their background”, added Mr Ng.

An investigator also acts as the key aggregator of information – not so much the subject matter expert.

“You will be supplemented by experts, such as aviation doctors, in their own field. Their views are really important to help you proceed with the case,” he explained.

“The investigator actually has a very prime role to aggregate all this information, provide an objective view of the occurrence and develop analyses to arrive at the conclusions.”

But there is one trait that could make or break a case – “an eye for detail”, he said.

“The devil is really in the details. Sometimes, being able to find that detail would mean a breakthrough in a case.”