Advertisement

Ow Siew Ngim’s favourite tree is the rain tree. (Photo: Jinee Chen/ CNA)

- A rover resembling Wall-E has been zipping around the Botanic Gardens and Jurong Lake Gardens recently

- With a laser scanner and cameras, it is making a digital copy of the gardens

- These and other tools help the National Parks Board’s tree doctors keep two million urban trees in tip-top condition

- A tree doctor explains how she learnt to ‘speak’ the language of trees

SINGAPORE: She was once drawn to animals such as monkeys and insects more than trees, which she thought were “quite boring”.

When she was a biology and tropical forest ecology student, Ow Siew Ngim would take “all the animal modules”. “We can learn a lot more because they move,” she said. “Studying behavioural patterns was so interesting when I was young.”

But trees became a sexier subject over time. “They just speak a different language from animals,” she said. “You need to interpret for yourself, … you need to confirm your inspection based on diagnostic tools and things (like that).

“I like the challenge.”

What made her see trees in a new light was a course conducted by the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA), a non-profit authority on the care of trees.

She went on to become a certified arborist and today is a streetscape and ops tech director at the National Parks Board (NParks). Keeping Singapore’s urban trees in tip-top condition is part of her job.

Of an estimated seven million trees in Singapore — a figure derived from tree censuses and past field surveys — NParks manages six million. The rest are managed by town councils and other parties such as private landowners.

Two million of the trees under NParks are urban trees along roads and in parks, gardens and on state land. The remaining four million are sited away from human traffic, such as in the remoter parts of nature reserves.

Urban trees are inspected every six to 24 months, with more frequent checks made on mature and heritage trees as well as those in certain locations, such as car parks and event spaces.

When explaining to the man in the street why trees need different levels of tender loving care, Ow often humanises her “patients”.

There are shorter intervals for some because “trees are like humans”, said Ow, who joined NParks more than 20 years ago and has been an arborist for over a decade. “Older people need more health screenings and check-ups.”

With more trees to be planted by 2030 under Singapore’s OneMillionTrees movement launched in 2020, NParks can expect “at least a 50 per cent increase” in trees it will be “actively managing”, she added.

Increasingly too, technology is lending NParks’ crew of over 250 arborists, also known as tree doctors, a helping hand.

HAVE YOU SEEN THE ROVER?

In recent months, eagle-eyed visitors to the Botanic Gardens and Jurong Lake Gardens may have spotted a rover that vaguely resembles Wall-E, the eponymous robot of the 2008 Pixar animated film, making its rounds.

With a laser scanner and two cameras mounted onto its red frame, the rover was on a mission to create “digital twins” of the trees at the gardens.

Operated by a (human) professional surveyor, it moves on rubber tracks similar to a bulldozer’s, enabling it to cover “practically any terrain”, said Greehill’s Asia-Pacific vice-president, Peter Sasi, whose tech firm co-developed the digital-twin technology with NParks and other partners.

“We don’t have to stay on the (paving); we can go off-road,” he said. “It (moves on) wide and … soft rubber belts, so it’s not hurting any of the greenery.”

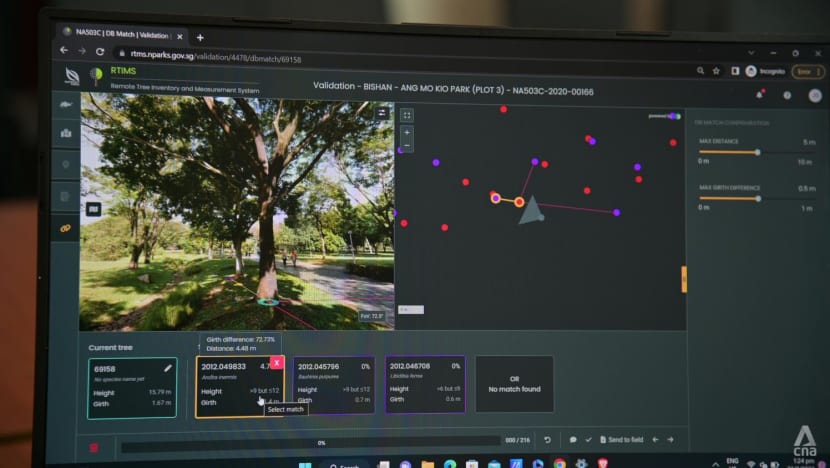

Using light detection and ranging (Lidar) technology, the scanner captures accurate measurements of each tree.

“We start by creating a complete digital copy of the entire park or entire streetscape,” said Sasi. “Everything is digitised in three dimensions and also with panoramic photos.”

A machine learning algorithm is then taught to identify trees and distinguish them from lamp-posts or signposts. It also establishes the geospatial location of each tree.

No longer needing to measure the tree’s girth and height or determine its location, tree doctors hope to cut the time needed for such an inspection by half, said Ow.

NParks’ remote measurements of trees were first done in the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio area in early 2021. But there was no rover at the time — the surveyors had to use trolleys to move the laser scanners and tripods, which weighed tens of kilogrammes.

By the time the project moved to the Botanic Gardens, the compact, industrial-grade electric rover had been added to the mix. By saving them time, it allows the arborists to focus on trees that “really need help”, said Sasi.

An NParks arborist may inspect about 400 to 500 trees in a typical month, and most trees are found to be healthy during first-level visual inspections based on international standards.

Very few trees are referred for second-level inspection, said Ow, without providing figures. (Besides trees with “possible defects”, NParks has also conducted advanced inspections of trees more than four metres in girth since November 2016.)

During advanced inspections, tree doctors will use decay detection instruments. For example, a resistograph drills through the trunk with a needle to measure the wood’s resistance, while a PiCUS sonic tomograph uses sound waves to investigate the tree’s internal condition.

Trees that are found to be unhealthy could be treated in various ways. Trees with yellowing leaves that are normally green could have mulch — dried leaves or other organic material — or fertiliser applied to them.

If part of a tree has structural defects, the defective part could be pruned. If an old tree needs additional support, cables and props would be used.

Trees deemed to be at risk of failure and pose a threat to public safety are removed and replaced.

FROM REAL HEAVY TO REAL TIME

Singapore’s trees have become more robust owing to measures, both tech and non-tech, put in place over the years.

From about 3,100 tree incidents in 2001, including branch snaps, the figure fell to about 480 last year. It has averaged about 400 cases a year since 2019. There will, however, be incidents “beyond our control”, Ow said.

Intense weather events include microbursts, which are columns of strong downward air that occur over a localised area within a thunderstorm and dissipate quickly.

According to the Meteorological Service Singapore, they are difficult to forecast but can result in winds of more than 270 kilometres per hour.

And when trees, as living things, encounter a force stronger than the wood can withstand, they will break, Ow said.

What we can do as humans is … our best: Have a standard regime, and follow it to a T.”

Since the early 2000s, NParks’ tree management has been anchored in a “rigorous regime of inspection and pruning”.

In the beginning, tree doctors used to head off to inspect trees with paper maps in hand, she recalled.

When the first mobile devices came along sometime after 2010, the arborists joked that the gadgets — used mostly for data updates — could double as weapons if they ever needed to defend themselves. Each weighed 1 to 2 kg, Ow estimated.

Today, the mobile devices used by NParks are a fraction of their predecessors’ weight and do much more. They let the tree doctors access details of each tree while in the field and update inspection records in real time.

Other tools in recent years include wireless tree-tilt sensors and the Tree Structural Model Plus, which is an algorithm that processes data on the stability of trees under different wind conditions, to guide NParks on how much pruning to do.

There are further improvements in store for the remote tree-measurement system.

NParks wants to use machine learning, artificial intelligence and digital twins to detect open cavities. It is also working on a height clearance tool to detect potential obstructions caused by low branches and ensure safe travel for tall vehicles.

‘SOLDIER-LIKE’ NO MORE

One reason that Singapore’s urban trees need more care than before is climate change: The island could experience effects such as more frequent and intense rainfall, prolonged drought and rising sea levels.

In 2012, NParks began reducing or thinning the crowns of trees before periods such as the southwest monsoon, which occurs from June to September and is marked by Sumatra squalls, a line of eastwards-travelling thunderstorms with strong winds.

In the past 20 years, NParks has also replaced diseased trees and storm-vulnerable species in forested areas abutting roads. Species such as the Albizia could be replaced with native species like the seashore mangosteen, which are better adapted to Singapore’s weather conditions.

And in corridors that connect key biodiversity areas, such as nature reserves, NParks now does multi-tiered planting to replicate the natural structure of forests as far as possible and facilitate the movement of animals between two green spaces.

In the past, trees were planted singly and “soldier-like”, which exposed them to the full force of the wind, said Ow. They are now accompanied by smaller trees and shrubs, which serve as buffers.

“What we’re trying to do is create a small forest ecosystem along the road to buffer our resilience against climate change,” she said.

What people may not know, however, is that Singapore’s regime goes beyond some international recommendations.

The ISA’s recommendation for tree inspections, for instance, is around every 24 to 36 months, cited Ow. And crown reduction should be 20 per cent or less.

But in Singapore, where trees compete with roads, footpaths and drains for space, there are times when trees must be pruned “not for routine maintenance but for clearance (such as for vehicle access)”, she said.

For Sasi, who is from Hungary and has lived in Singapore for about eight years, what is gratifying is the use of technology to help cities remain liveable in a hotter world.

Greehill has projects in other countries including Austria, and he hopes his work will have an impact on the future of his two children in preschool.

“I’m working on some cool tech stuff and also helping the future of my kids to be more survivable, more livable,” he said.