For an event that bills itself as the most beautiful race in the world, the Mille Miglia is a surprisingly difficult, dirty, dangerous affair. I finished my third competitive outing there in June, this time behind the wheel of a bewitching 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing, owned by the marque’s museum in Stuttgart and worth perhaps $1.8 million. After each event, I’ve handed the keys to my priceless vintage car back to the crew with a sense of relief and disbelief that both it and I were still in one piece and wondered if I’d have the nerve to do it again.

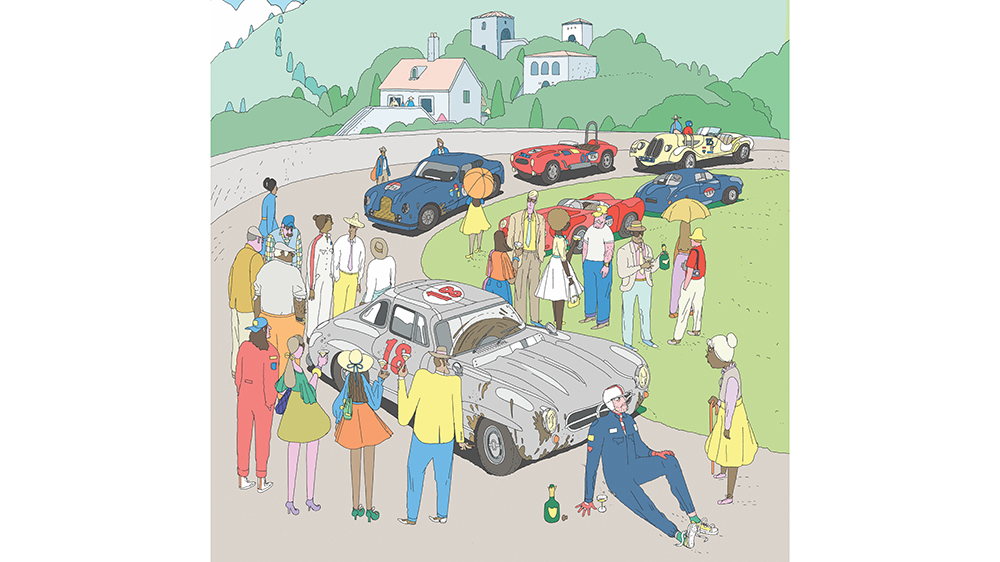

You’ll have read other accounts of this extraordinary vintage rally along the length of Italy. But for some reason, possibly out of a sense of duty or quid pro quo toward whichever watch or car company was sponsoring their endeavors, most journalists seem reluctant to really capture the bureaucracy, the confusion of the rules, the extreme fatigue of driving for 16 hours a day for four days, on three hours’ sleep a night, and the all-too-frequent sense of imminent doom as 400 vintage cars with values often deep into the millions barrel flat-out over 2,000 kilometers of open public roads, in complete defiance of the law but with the active encouragement of both the carabinieri and the local populace, who come out to cheer you on as you do 100 mph through their school zones.

It could only happen in Italy, and there is nothing else like it in the collector car world. But it’s really hard work. I’d wondered, after my previous races, why so many million and billionaires fight to secure entry, paying premiums for classic cars which are already worth millions of dollars because they’re more likely to be admitted, and often spending well into six figures on four days of driving once you include the cost of preparing your vehicle and transporting and accommodating your support crew. But this year, as I scrubbed the sweat and grit and scent of oil and brake and clutch from the back of my neck in my hotel in Brescia, the answer came to me.

Firstly, the briefest of recaps. As the name suggests, the original Mille Miglia was a race run over miles of public roads, from Brescia in the north to Rome and back again. It was held between 1927 and 1957 and was dangerous enough for Mussolini to ban it in 1939 and from 1941 to 1946. It was finally officially prohibited in ’57, when the Ferrari helmed by Spanish-Irish nobleman, racing driver and playboy the Marquis de Portago blew a tire at speed and crashed into the crowd, killing him, his co-driver and nine spectators, including at least two children.

An accident on that scale had been on the cards for some time. The great Nuvolari was so exhausted by the Mille in ’48 that he had to be carried from his early Ferrari—which was also rapidly disintegrating—into the cool gloom of a church to recuperate. Stirling Moss admitted that he’d needed amphetamines to cover the route in a fraction over 10 hours at an average speed of almost 100 mph in 1955 in his Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, which remains one of the greatest drives in motorsport.

The race was revived in 1988 as an historic rally for cars that could have competed in period, and while in theory you can do the entire route within the speed limit, that’s very much not how it works in practice. If you get lost or break down or struggle to find fuel, you end up driving flat-out to arrive at the next checkpoint on time. And even if you’re not late, you end up driving like that anyway, swept up in the manic exuberance of the event. Usually flashing blue lights in your wing mirrors are a very bad thing when you’ve been driving “enthusiastically,” but on the Mille it just means you’re going to have a police escort for the next few miles and can dive into roundabouts with just a brush of the brakes and without checking for traffic because you’re at least reasonably confident that your police outriders have stopped it.

This goes on all day for four days until you are deliriously tired. And that’s the point, I think. It’s a peculiar sort of luxury experience, but the tiredness is what you’re paying for.

There’s nothing else you can do with your classic racer that really makes you feel how your heroes did when they were driving cars like yours in period. It’s very nice to park your ’30s Alfa or ’50s Ferrari on the lawns of Pebble Beach or Villa d’Este and let people admire it while you drink Champagne, but that’s not what it was made for. Historic racing on circuits gets closer, but it can be tame and is more likely to expose your lack of ability than make you feel like Moss or Nuvolari.

But the Mille can. It’s the same crowds who come out to wave you on, though I spied one elderly lady spectating from her balcony who eyed me cynically, as if to say that she remembered Moss in ’55 and I was no Moss. It’s the same fear of a crash: my Gullwing’s sole concession to safety being the tiny chrome grab handles on the dash which were too bloody hot to grab anyway. Drivers have died in the historic version of the Mille, and I know people who have sustained serious injuries. And sure, you’re doing it in four days rather than in one, but it’s a similar kind of exhaustion. Now you rely on caffeine rather than amphetamines to finish each day. You sometimes wonder if it’s enough, but you neck another doppio and carry on.

I don’t expect you to feel sorry for the competitors, though. There are more than enough transcendent moments to compensate for all the entirely voluntary hardships, such as when a setting Tuscan sun turns that glorious long silver hood polychromatic as you arc through the Apennine Mountains, or when that same hood rises up as you give the Gullwing its head and blare hard and fast and free down the endless straights through the cornfield plains between Milan and the finish line at Brescia. When I got there, I slept for 13 hours, wondered again if I’d risk my neck if asked a fourth time and pretty quickly reached the same conclusion.

Ben Oliver is an award-winning automotive journalist who writes from the UK.